magine you're standing in a dry, remote area. A community needs a new well, but they only have the budget to drill once. Drill in the wrong spot, and they hit dry, solid rock—wasting their entire budget and leaving them without water. How do you "see" hundreds of meters underground to find the one narrow fracture zone holding water? You can't. But you can use physics. You lay out a transmitter and loop of wire (an EM system) and "ping" the earth with a magnetic field. Your receivers on the surface record the "echo"—a set of complex, noisy numbers.

Now what? You have the data, but you don't have the map. The critical step missing is the inversion: a powerful algorithm that can take those raw numbers and work backward, building a 3D model of the subsurface that must have created them. That algorithm is the engine that turns cryptic data into actionable discovery. This post is the step-by-step guide on how to build that engine from first principles.

This post builds a modern EM inversion from the ground up. We start with the core physics and construct the heart of the problem: a stable objective function that balances fitting your data with known geological constraints.

From there, we derive the inversion "engine"—the Gauss–Newton / Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. We then reveal the key insight: how this exact same logic scales from a simple 1D solver to a full, matrix-free 3D model. Along the way, we cover the practical details of data weighting, regularization, and diagnostics needed to produce a trustworthy result.

What is Inversion, and Why Do We Need It?

efore we write a single line of code, let's start with a simple question: How do you see something you can't touch?

Let's assume you're on a boat in a thick fog. You can't see the seafloor, but you have a sonar system. You send a "ping" (a sound wave) into the water. This is the "forward problem"—using known physics to predict what will happen. A few seconds later, you hear an echo. That echo is your "data". Your brain instantly does the math: "Based on the echo's timing and strength, the seafloor must be 100 meters deep and rocky." That mental calculation—turning observed data back into an unseeable model of the world—is the essence of inversion.

A doctor uses a CT scanner for the same reason. They can't see inside your body, so they pass X-rays (physics) through you and measure what comes out (data). A powerful computer then inverts that data to build a 3D model of your insides. Numerical Inversion is our "CT scanner" for the Earth. It's the mathematical and computational process of taking our limited, noisy measurements from the surface and using them to build a reliable picture, or "model," of the Earth's invisible subsurface.

Okay, So What is EM Inversion?

“Inversion isn’t magic — it’s physics, optimization, and honest uncertainty.

”

Instead of sending a sonar "ping" or X-rays, we use electromagnetism (EM). An EM inversion does this:

- Transmit (Forward Physics): We generate a controlled electric and magnetic field, which soaks into the ground. This is our "ping."

- Measure (Data): We use sensitive receivers to record the tiny secondary fields that the Earth sends back. Different materials (like fresh water, saltwater, ore bodies, or oil) all respond differently.

- Invert (The Model): Our algorithm—the one we're about to build—takes these measurements and solves the puzzle: "What 3D model of electrical conductivity underground is the only one that could have produced the exact data we just measured?"

Why It Matters: From Water to Minerals

This isn't just an academic exercise. EM inversion is the engine behind finding:

- Groundwater: Locating fresh water aquifers to drill wells for communities.

- Critical Minerals: Identifying deposits of copper, lithium, or nickel needed for batteries and green technology.

- Geothermal Energy: Mapping hot rock and fluid reservoirs to generate clean power.

- Environmental Safety: Monitoring how contaminants are spreading from a spill.

In all these cases, drilling is expensive and risky. Inversion is what lets us "drill" a thousand times on a computer first, so we only have to drill once in the real world. Now, let's build the engine.

Step 1: The Forward Model & The Objective

his is the "sonar ping" for our problem. In geophysical inversion, we first need a "Forward Model"—the physics that predicts what we should measure. For frequency-domain EM, that physics is governed by the vector wave equation.

This equation is our workhorse. It describes how an electric field (our "ping") interacts with the subsurface. The key is the term , which contains the Earth's properties: . This means if we change the conductivity (our model), the equation gives us a different predicted response (our data).

We can summarize this whole physical simulation with one simple function: . You give it a model (the conductivity map), and it returns the simulated data . That's the forward problem. Now for the inverse problem. We already have our real measurements, . Our goal is to find the one model that is:

- Accurate: It must successfully predict our real data. ()

- Plausible: It must be geologically reasonable (i.e., smooth, not a spiky, chaotic mess).

We enforce this balance by creating a "score," called the Objective Function (), that we try to make as low as possible. It has two parts:

Here, is the Data Misfit, which measures how badly our prediction matches the real data (the error). is the Regularization (or "model cost"), which penalizes models that are too rough or complex. The value is a simple slider that "trades off" the two: do we care more about a perfect data fit or a smoother model?

The entire goal of our inversion is now simple: find the single model that makes the score as low as possible. The next steps will show the exact algorithms (Gauss-Newton and Levenberg-Marquardt) we use to find that minimum.

Defining the "Physics" in our Forward Model

Okay, let's get specific. Our "Forward Model" isn't just an abstract idea; it's a specific piece of physics. For most EM surveys, the workhorse is the diffusive form of Maxwell's equations. This is a common simplification of the full wave equation we saw in Eq. (1). At the lower frequencies we use in geophysics, the "conduction current" () is dominant, and the "displacement current" () is so tiny we can safely neglect it. This gives us our practical, workhorse PDE:

This equation is the core of our function . It directly links the property we want to find—the conductivity (our model )—to the electric field that we can measure. This "diffusive" physics gives us a crucial rule of thumb for understanding our problem: the skin depth.

The skin depth tells us how far our EM "ping" can penetrate the earth. Any geological features much smaller than will be invisible or "smeared out," and features much deeper than won't send an echo back. This simple formula is our first reality check for survey design and for deciding if a simpler 1D or 2D model is good enough, or if we need to use a full 3D simulation.

From Physics to Data: What Instruments Measure

ur forward model (Eq. 3) predicts the full electric and magnetic fields everywhere in the ground. But we can't measure that. We can only measure a few components at specific receiver locations on the surface. Our instruments record these surface fields and convert them into robust, interpretable ratios. For MT/AMT/CSAMT, this gives us two key pieces of data:

- The Impedance Tensor (): This is the primary data. It measures the ratio of the horizontal electric fields to the horizontal magnetic fields that induced them: .

- The Tipper (): This measures "tipping" of the magnetic field, linking the vertical component to the horizontal ones: .

Different methods (like FDEM or TDEM) might record field components directly. But in all cases, these measurements—, , or raw fields—are all just different "views" of the same underlying physics. They are the observed data that our inversion will try to match.

Choosing Your "Physics": 1D, 2D, or 3D

Our forward model has to solve that PDE (Eq. 3). The cost and complexity of that solve depend entirely on the "dimensionality"—the assumptions we make about the Earth's geometry.

-

1D (Layered Earth): 🥞 We assume the Earth's properties only change with depth (). This is a huge simplification! The PDE reduces to a super-fast calculation (a Hankel transform). This is perfect for quick checks, simple geology, or getting a fast first look at the data.

-

2D (Across-Strike Structure): 🏞️ We assume properties change with depth () and one horizontal direction (), but are constant in the third direction (). This is a great compromise, ideal for long, linear geological structures like valleys or fault lines. We solve the PDE on a 2D mesh, which is much more computationally intensive than 1D but still manageable.

-

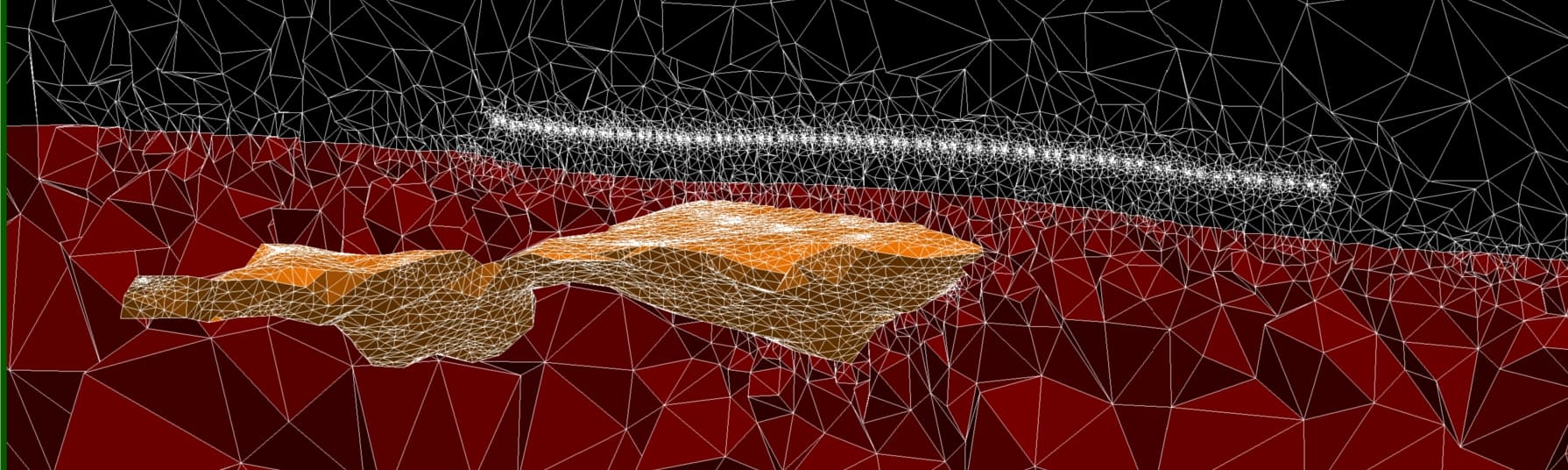

3D (General Geology): 🧱 This is the full, no-compromise solution. We assume properties can change in all directions (). This requires solving the PDE on a massive 3D grid and is computationally brutal, demanding large computers and clever algorithms (like matrix-free solvers).

Crucially, the inversion algorithm we'll build in the next steps is agnostic to this choice. The only part that changes is the "physics engine"—the 1D, 2D, or 3D forward solver we plug into it.

Model parameterization you will invert

We invert for to enforce positivity and to make steps multiplicative in . The numerical meshes (1D layers, 2D/3D cells) are model grids; survey-specific data (impedances, fields) are predicted at receiver locations via interpolation and functional evaluation. Sensitivities are with respect to : the Jacobian is what couples physics to optimization.

The objective we minimize

Inversion balances two forces: fit the data you trust and stay geologically plausible. We encode this as a sum of a weighted data misfit and a model regularizer:

scales each datum by its uncertainty (and optional error floor). If a standard deviation is known, a common choice is , so that a “good” fit corresponds to a normalized near 1.

promotes structure you expect in the earth. For smooth Tikhonov regularization, stacks zero-order and first/second differences, e.g. . You can also switch to total-variation (TV) for sharper contacts, or include a reference model to pull solutions toward known geology.

trades off fit and smoothness. We typically start with a larger (stability first), then reduce it (“cool” it) until the data misfit reaches the noise level—this is the discrepancy principle, aiming for .

To use gradient-based solvers we need the derivative of with respect to the model:

Here is the sensitivity (Jacobian) and is the residual. In 1D we can often form explicitly; in 2D/3D we apply and implicitly via forward/adjoint solves—critical for memory and speed.

Robust options (when outliers show up)

The quadratic misfit is optimal for Gaussian noise. With spikes or static shifts, replace the squared norm by a robust penalty , e.g. Huber or Tukey. This preserves sensitivity near zero but limits the influence of outliers, improving convergence and model stability.

Practical checklist

• Set reasonable error floors in (e.g., 5–10% amplitude, 1–2° phase).

• Choose to match geology (smooth vs. blocky), and supply

when you have trusted prior information.

• Schedule : start high, reduce by a factor 0.5–0.8 until

hits the noise level.

• Work in to enforce positivity; apply bounds via

projection if needed.

What comes next

We now turn the objective into an algorithm. The core idea is simple: linearize the forward map around the current model, solve for a model update that reduces the objective, and repeat. This leads to the Gauss–Newton / Levenberg–Marquardt (GN/LM) system:

The matrix on the left blends three ingredients: the data curvature (how changes in the model affect data), the regularization curvature (how changes affect roughness), and the damping which controls step size. When we recover pure Gauss–Newton; when is large, the step behaves like a cautious, well-conditioned gradient descent. After solving for , we accept a scaled step with a line search or trust-region rule and update and adaptively.

In Step 2 we will derive this system carefully and implement it in practice:

- 1D layered earth. We exploit fast Hankel-based forward models and either analytic sensitivities or cheap Jacobian–vector products. This gives rapid iterations, great for QC and for building intuition about depth of investigation.

- 2D and 3D. We move to PDE solves on meshes. We never form explicitly:

gradients come from adjoints, and the left-hand side in

Eq. \ref{eq:gn-lm}is applied matrix-free using Krylov methods (CG/LSQR). Good preconditioners and a sensible schedule are the difference between minutes and days.

By the end of Step 2 you will have a working GN/LM loop that hits a target misfit (discrepancy principle), respects bounds in , and produces models that are both geologically plausible and quantitatively justified.

Step 2 — From objective to updates (Gauss–Newton / Levenberg–Marquardt)

e turn the objective into an algorithm. Linearize the forward map around the current model: . With this quadratic approximation, minimizing yields the normal equations:

The right-hand side is the gradient with residual . The three terms on the left are the data curvature, the regularization curvature, and the damping . Small gives a Gauss–Newton step; large behaves like a cautious gradient step.

Accepting the step: line search or trust region

Solve for (usually with CG/LSQR, matrix-free). Then choose a step length by an Armijo backtracking line search, enforcing bounds in if present. Trust-region LM variants adapt using a gain ratio:

If is high (the quadratic model predicted the decrease well), decrease and allow bolder steps; if is poor, increase and retry with a smaller step. This keeps the iteration stable even when the linearization is imperfect.

Scheduling (fit vs. stability)

Start with a larger to stabilize early iterations, then reduce with once the misfit drops. The target is the noise level: for a good fit.

A minimal 1D GN/LM loop (pseudocode)

import numpy as np

def phi(m, beta, Wd, Wm, F, d):

f = F(m); r = f - d

phid = 0.5 * np.linalg.norm(Wd @ r)**2

phim = 0.5 * np.linalg.norm(Wm @ (m - mref))**2

return phid + beta*phim, phid, phim, r

m = m0.copy(); beta = beta0; mu = mu0

for k in range(max_outer):

f = F(m) # forward

r = f - d

J = J_1d(m) # analytic or fast JVPs

g = J.T @ (Wd.T @ (Wd @ r)) + beta * (Wm.T @ (Wm @ (m - mref)))

# Left-hand side operator (apply via CG for large problems)

A = J.T @ (Wd.T @ (Wd @ J)) + beta*(Wm.T @ Wm) + mu*np.eye(m.size)

dm = solve(A, -g) # Cholesky small; CG/LSQR large

# Backtracking line search with bounds in log-sigma

alpha = 1.0

while alpha > 1e-4:

m_trial = project_bounds(m + alpha*dm, lb, ub)

phi_old, phid_old, _, _ = phi(m, beta, Wd, Wm, F, d)

phi_new, phid_new, _, _ = phi(m_trial, beta, Wd, Wm, F, d)

if phi_new <= phi_old - 1e-4*alpha*np.dot(g, dm): # Armijo

m = m_trial

# LM gain ratio (optional): update mu

denom = 0.5 * dm @ (A @ dm)

rho = (phi_old - phi_new) / max(denom, 1e-12)

mu = max(mu * (0.33 if rho > 0.75 else (3.0 if rho < 0.25 else 1.0)), mu_min)

break

alpha *= 0.5

# Reduce beta once the normalized misfit is near 1

if phid_new <= 0.5 * N_data:

beta *= 0.7

if np.linalg.norm(alpha*dm) < 1e-3 or k == max_outer-1:

breakThis 1D loop is intentionally compact: it mirrors the exact logic we will reuse in 2D/3D, where matrix-free products replace explicit matrices and a preconditioned CG solves the normal equations. Next, we will plug this engine into a 1D layered forward model to recover a simple conductive basin—then scale the same algorithm to 2D and 3D.

Step 3: 1D Inversion in Practice — Recovering a Conductive Basin

et's put the algorithm from Step 2 to the test. We'll define a simple 3-layer "true" model: a resistive layer (100 m), followed by a conductive basin (10 m), over a resistive basement (1000 m). We generate synthetic data from this model using our 1D forward solver, add 5% Gaussian noise to simulate a real survey, and then feed these "observed" data to our inv1d_gnlm function. We'll start the inversion from a simple, uninformed 100 m half-space.

The solver converges in just a few iterations. It starts with a high , finding the coarse structure first (as seen in the early iteration models). As the data misfit approaches its target (the discrepancy principle), the algorithm automatically reduces , allowing the inversion to fit the finer details. The final recovered model clearly resolves the conductive basin, demonstrating that our optimization loop is stable and effective.

Step 4: Scaling to 2D and 3D (The Matrix-Free Approach)

ere is the most powerful idea in numerical inversion: the optimization algorithm we wrote for 1D does not change when we move to 2D or 3D. The inv1d_gnlm.py pseudocode, with its while loop, Armijo search, and schedule, is the exact same engine we use for 3D inversions with millions of parameters.

The only thing that changes is how we compute the four key components:

- (Forward solve): Instead of a fast 1D Hankel transform, this is now a large PDE solve on a 2D or 3D mesh (e.g., using finite-volume or finite-element methods).

- (Residual): This is identical. We just compute the difference.

- (Gradient): We never form the massive Jacobian . Instead, we compute the full gradient (Eq. 6) using an adjoint-state solve. This is a well-known technique that gives the complete gradient for the cost of just one extra forward-like solve, regardless of the number of model parameters.

- (System Solve): We now solve the GN/LM system (Eq. 7) using a matrix-free Krylov solver like Conjugate Gradient (CG) or LSQR. These solvers don't need the matrix itself; they only need a function that, given a vector , returns the product . This is perfect for us, as computing that product only requires a few (e.g., two) forward/adjoint solves per CG iteration.

Conclusion: A Unified Optimization Engine

e've built a complete mental model for EM inversion. We started with the forward physics (Eq. 2), defined a stable, weighted objective function (Eq. 5), and derived the workhorse Gauss-Newton / Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (Eq. 7) to minimize it.

The key insight is that the optimization logic is separate from the physics implementation. By using adjoints for gradients

and matrix-free solvers for the update step, the same algorithm scales from a 1-second 1D model to a 10-hour 3D inversion.

This modularity—separating the minimize(Objective) from the Objective.compute(gradient, residual)—is the core of all

modern geophysical inversion frameworks.